High Expectations, High Support: The Heart of Trauma-Informed Practice

Trauma-informed practice is not about lowering expectations for someone just because they’ve experienced trauma. Low expectations are not a kindness—they’re harmful. They send the message that someone is incapable, they reinforce negative views the person may already hold about themselves, and they say “You’re right, you’re not worth challenging”.

What trauma-informed practice is really about, is holding high expectations and offering high support. It’s about seeing where someone is at, understanding their needs, and providing the right scaffolding to help them move forward. It’s about saying, “I believe in who you could become, and I’ll be here to help you get there.”

Defining Expectations and Support

To understand why both high expectations and high support matter, it helps to break them down. Here’s how we view them:

High Expectations: Holding someone to a standard that challenges them to grow, believing in their potential, and not assuming their circumstances define their future.

High Support: Providing the necessary guidance, encouragement, and resources to ensure they have what they need to meet those expectations.

Low Expectations: Assuming someone is incapable, setting the bar too low, or not challenging them to grow. This can reinforce helplessness and stagnation.

Low Support: A lack of the necessary scaffolding, resources, or opportunities that enable someone to succeed. It can mean failing to remove barriers, not providing clear structures, or offering insufficient guidance.

The Four Quadrants of Expectations and Support

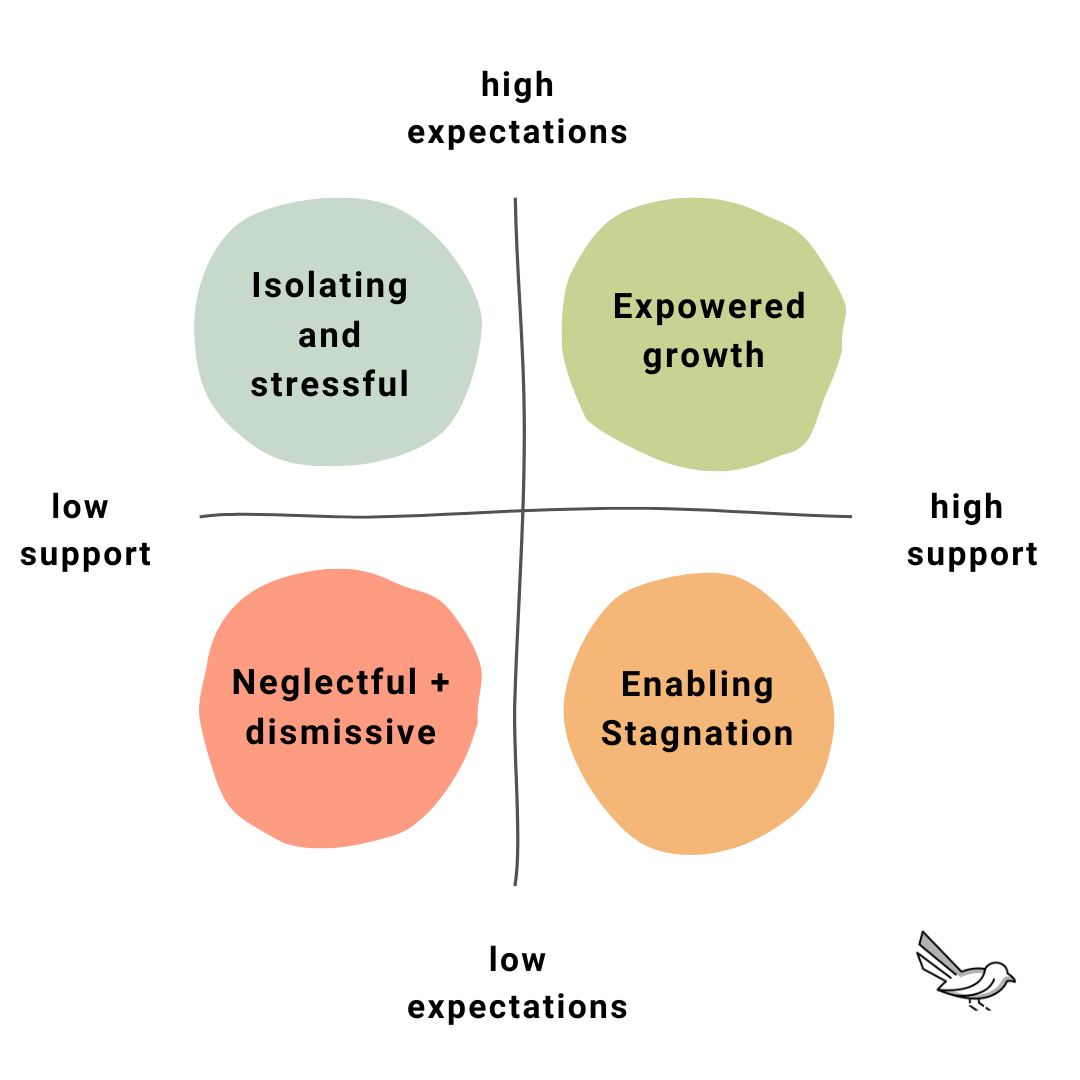

A trauma-informed approach balances high expectations with high support. When one is missing, we can unintentionally disempower people. Here’s what the balance (or imbalance) looks like:

Figure 1: Expectations and support, Wagtail Institute

High Expectations, High Support in Action

When I was a school leader, a large part of my work was supporting young people in restorative practices. I remember one young man who enrolled in our school who engaged in a record number of restorative meetings.

It felt like I was always on my toes, hearing from others that something had gone wrong, spending my day trying to find him and work through what was going on.

But I also knew nobody in his life had supported him in navigating conflict and repair before.

I knew that he was bouncing between staying with different family members and had been rejected from other schools. So, we kept doing it. We kept meeting. We kept unpacking what had happened. How we could repair. How we could regulate next time. What support he needed.

And eventually, something amazing happened.

I didn’t have to chase him anymore. He started knocking on the office door, letting me know he felt dysregulated and asking to punch some pads or go for a walk. He even started letting me know when he needed to repair with someone. Soon after, we were meeting less. Eventually, we weren’t needing those meetings at all.

This is what high expectations and high support look like in action. Holding space for someone, guiding them, and trusting that the work you put in together will lead to growth.

The Risk of Over-Accommodating: “Enabling Stagnation”

I was reminded of this recently when I spoke with a young person at an alternative school. He told me attending an alternative school had changed him in ways that weren’t all positive. While he reflected that he was better able to manage his emotions, to form relationships, and explore his interests, he felt like he was letting himself down, too.

He had come to realise that if he wanted to get out of work, all he had to do was say he was tired or angry, and his teachers or support workers would let him take time out. While he appreciated their kindness, he felt like they never challenged him, so he began to report tiredness or anger even when that was far from how he felt. The situation had made him complacent. He used to love being challenged, and he missed feeling capable.

We had a conversation about accountability. About setting goals. About the balance of support and expectations. He wanted to tell his teachers about this, so we planned ways he could start that conversation.

His teachers and support workers had good intentions. They had been trained in trauma-informed practice (obviously not with Wagtail Institute ;) ), yet they were struggling to match their high support with the right level of challenge.

This is why high support without high expectations is not truly trauma-informed. It can create a cycle where young people feel comfortable but unchallenged, leading to stagnation rather than growth.

Finding the Balance

To be trauma-informed, we have to find that sweet spot in supporting people and moving beyond comfort. It’s a skill and it takes a little experimenting. It means saying:

“I believe in you. I believe in your future. And that means I’m going to push you, even when it feels uncomfortable. But I’ll be here supporting you through that discomfort, every step of the way.”

This balance of high expectations and high support is what truly empowers people to grow, heal, and reach their potential.

Upskill and enhance your practice with Wagtail Institute

When workplaces are truly trauma-informed, we see good outcomes for their entire communities. So before slapping the terms on our taglines, let’s ensure we’re integrating this approach responsibly and effectively.

Creating a trauma-informed workplace where staff feel safe, supported, and competent requires a multi-faceted approach, a new perspective and way of being with each other. It’s not just a bunch of catchy words.

We work alongside leaders, teachers, social workers, and a variety of practitioners to respond to wellbeing challenges, enhance trauma-informed practice, and navigate pathways to healing.

If you are curious about what this could look like in your setting, schedule a free consult call with Megan.